Wax and Fiber is the focus of the Winter 2015/2016 issue of Surface Design Journal. And from what I can tell, it is a juicy one! Chock full of stories and images by and about artists who work with wax sourced at the International Encaustic Conference. Check out a sample here.

Wax and Fiber is the focus of the Winter 2015/2016 issue of Surface Design Journal. And from what I can tell, it is a juicy one! Chock full of stories and images by and about artists who work with wax sourced at the International Encaustic Conference. Check out a sample here.

A series is a set of individual artworks connected by a theme. A series can be short and immediate (all the monotypes made in a single day). Or it can unfold over a period of years. Either way, working in series is a way to go deep.

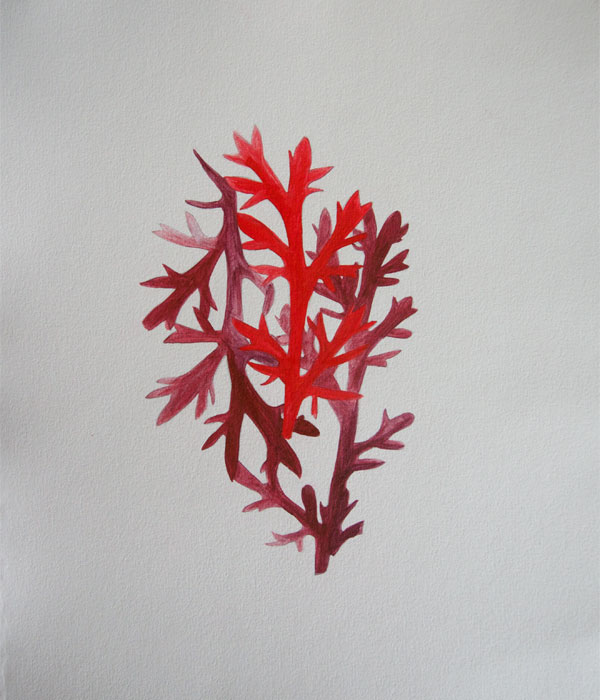

A handful of pieces from One-Hundred Flowers. When I work in series I’m working with ambition and thinking about scale.

The simplest way for an artist new to working in series to get going on one is to choose a single format – a single canvas size, or size and color of paper – and stick with it and see what happens. The more limits you set, the more interesting the results you get will be.

Learning the Rules

There are as many ways to set limits and work in series as there are artists. I start with an image in my mind’s eye and go through a process I call learning the rules where I teach myself how to make it through trial and error. Like a memory of a dream, the mind’s-eye-image morphs as I add details in an attempt to pin it down. That is OK. I am working to join the imagined with the real at this point. Some give and take is fine.

In the two test images above I’m asking questions about overlap. Which degree of overlap moves the image closer to the one in my mind’s eye? Is overlap relevant to what I’m trying to do? Once I have an answer I can make a rule/set a limit about overlap. (I know this sounds deliberate but in practice the process feels intuitive.) Moving forward, I can keep limits or break them. But I absolutely enjoy being able to articulate them. Limits enable consistency. And on another level, they help me understand what my work is about.

What LImits Mean

The thing that excites me about limits, and part of what I hinted at in Art Practice vs. Play, is how the process, or practice, of setting limits is meaningful. Each limit you choose provides a glimpse into your interests, and into what you value as an artist. As the limits you choose for your work accumulate, what they signal becomes more compellingly specific. If you’re working intuitively (as I do with mind’s-eye-images) then setting limits is a way to bring the unconscious to light. And finally, by setting limits for your work, you are making your values visible. Your viewers may not be able to articulate what they are, but if you’ve thought about it, you will be able to. This will deepen what you understand about your work. And it will help you talk about it.

A painting in my shop.

Midwinter can feel like an empty time in the studio because the subjects I most love to draw, low-growing plants with interesting leaves, are typically dormant or covered by snow.

But this month I’m feeling lucky (and the studio feels full)! Because there’s a green patch of yarrow in our garden that’s stayed accessible between snows.

I am in love with this plant because it’s feather-like leaves have a branchy, tree-like quality.

Wondering how many days there are until spring? Let this countdown tell you. (As of this writing, it says sixty-one days to go.)

If you’re an artist who thinks of your work as play, or who has referred to your work in the studio as playtime, I’d like to invite you to think differently, and go deeper this year. It’s not that play doesn’t happen in the studio. It does! Play fosters risk-taking, discovery and flow. And it’s worth doing for the fun alone.

John Cleese, insightfully, on the relationship between play and creativity.

Play is serious business for children, a deep, imaginative mode that facilitates learning. But when adult artists use the word ‘play’ to talk about what they’re up to in the studio, it comes off as breezy shorthand for pleasure that means “I did something fun.” If you’re using any of the #studioplay hashtags on social media you’re calling on a stereotype of the artist as a childlike figure content to mess around with paint. It’s inauthentic. (I know that’s not who you are. No artist is.) And it fails at communicating the juicy, more interesting stuff about who you are and what you do.

Meaning

Art is fun (when it’s going well). There’s a narcissistic, almost primal pleasure in seeing something of yourself reflected back at you in a mark you’ve made, whatever that mark may be. I get that. It’s part of the draw. But it’s not why I chose art. I chose art as my vocation, and have chosen it again and again at the crossroads in my life, because it holds meaning for me.

Jackson Pollock painting for the camera. Is this work? Play? Or is something else going on?

Unfortunately, the meaning I get out of art isn’t constant. Sometimes my work feels guided and purposeful. Other times it’s a struggle. I don’t see art as special in this way. This is something that all of us who want to do meaningful work have to face. When I think of what I do in the studio as play in the service of enjoyment, when I dismiss the more challenging work I feel called to do, or that is required of me by deadlines, then purpose fades.

Practice

I like the word ‘practice’ for what happens in the studio because of its many meanings. Practice connotes seriousness. A doctor works in a medical practice. An attorney practices law. But it’s also linked to play. A musician has to practice before she can play a new instrument. Athletes practice before they play. And then there’s the spiritual angle. You can practice your religion. Or start a meditation practice. In all cases ‘practice’ suggests an ongoing commitment to a growth oriented endeavor. To have an art practice is to engage with your work and your materials in a complete way, physically, intellectually, spiritually. Play may be a part of your process. But it’s not the most interesting thing you do.

Joanne Mattera, painter and author of The Art of Encausitc Painting, posted a terrific nuts and bolts essay over the weekend that clarifies some of the confusing information floating around about encaustic paint. If you’re confused about the difference between encaustic and cold wax medium (they are not the same, nor are they compatible); wondering how to describe your image transfer work (many choices but avoid the trendy and misleading ‘photo encaustic’); or seeking an up-to-date list of encaustic resources, you will find 10 Things I Know for Sure About Encaustic an interesting read.

In 2015 I read two books in conjunction with each other that had a powerful effect on me. If you’ve struggled in the last year to prioritize multiple, complex projects; if you feel pulled; if you have the sense that your actions are out of whack with what matters most but you’re not sure exactly how, then it’s my pleasure to recommend Fierce Medicine by Ana Forrest, and Get It Done by Sam Bennett to you. Individually, they’re both interesting books in the self-help vein. Together they have a synergistic quality that may help you renew your sense of purpose.

Part memoir, part yoga manual and part self-help guide, Fierce Medicine is made potent by author and yoga teacher Ana Forrest’s willingness to lay her flaws bare. Forrest, the survivor of a youthful suicide attempt that proved a watershed moment on her path to becoming a yoga guru, tells her story of enduring terrible pain, emotional and physical, before learning to “stand straight.” At the emotional heart of Fierce Medicine is a writing exercise called the Death Meditation. I know it sounds depressing, but it is not! I did it and found it deeply moving. There’s something about Forrest’s writing, her rawness and openness, that can open the reader to her teaching, fierce as it is. After doing the Death Meditation, false priorities, things I thought were important but really weren’t, fell away. And a renewed commitment to specific aspects of my work and life as an artist emerged. Highly recommended.

A light, playful read, Get It Done by Sam Bennett is the tonal opposite of Fierce Medicine, and a wonderful complement to it. In a method that reminds me of the one David Allen outlines in his excellent book, Getting Things Done, Sam Bennett coaches readers through overwhelm with a series of exercises that aim to help prioritize and break ambitious projects into doable, 15-minute chunks. Bennett’s writing voice is casual, friendly and fun. A creative person herself, she gets what it’s like to have many projects in various stages of undo. If you struggle to get projects across the finish line because perfectionism and/or procrastination, then is the book for you. I found it grounding to read at the same time I was working through Fierce Medicine.

May you find joy and readiness during this week between Christmas and New Year’s. It’s a special one! My favorite of the year. While I’m not much of a resolutions person I do take it in earnest as a time to rest, enjoy and prepare.

It was my recent pleasure to host a holiday supper for two artist friends whose company I adore. Our thing, when we get together, is to assemble a snacky feast that very often centers on soup. This particular gathering called for something festive that honored the season but that was also hearty and casual. Dream of Carrot hit the right notes. Its bright yellow color is cheerful and the addition of peanut butter adds a hearty/umami flavor that defies expectations.

Recipe, Dream of Carrot Soup

Adapted from a Daily Camera recipe I clipped years ago. Author unknown.

Ingredients

1 large onion chopped (about 1.5 cups)

1 heaping tsp cumin

1 dash cayenne pepper

1 tsp fresh grated ginger

2 T olive oil

Salt to taste (1 to 2 tsps)

3.5 cups of chicken stock or water

2 pounds carrots, roughly chopped

2 medium potatoes (russets are good), roughly chopped

1 tsp honey

3 T natural peanut butter

Method

Warm olive oil in a large soup or stock pot over medium heat. Add the onions, ginger and spices and sauté until soft.

Add salt and stock (or water if you’re cooking for vegans), carrots and potatoes and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer until everything is very soft, about 25 minutes.

Remove from heat. Stir in honey and peanut butter while soup is still warm.

Wait for the soup to cool to a safe blending temperature before transferring in batches to a blender or food processor. Blend until smooth.

Return blended soup to cooking pot. Reheat, stir, and adjust seasonings to taste.

Serve hot with pepitas or blue corn chips.